The Honorable Shelley Moore Capito

170 Russell Senate Office Building

Washington, DC 20510

Dear Shelley:

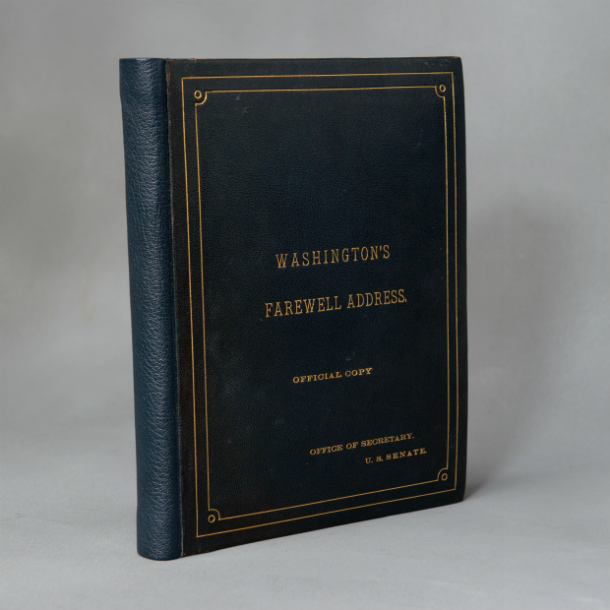

The purpose of this missive is to request of you to sponsor my GEORGE WASHINGTON FAREWELL ADDRESS REVIVIFICATION AND PRESERVATION ACT in the Senate.

As you may recall, 18 years ago, I wrote you to request your assistance with my dream of bringing George Washington back to Washington. Despite your having forwarded the materials to my then-state senator, Clark Barnes, he apparently had absolutely no interest in promoting George Washington's farewell address in the state Senate and thus introduce the resolution in hopes that our then-US senator, the Honorable Robert Byrd -- the same senator who I personally observed in the chamber attentively reading hardcopy when the farewell address was read aloud like it really meant something to him-- might consider taking it to the floor of the U.S. Senate. But now, that distinctive honor is yours for the taking.

I was so disheartened by a non-response of neither acceptance nor rejection that I stood down from my cause with my head hung low. How far has our country sunk to the point that no one seemingly cares about its #1 Founding Father? He proved it. I can't believe he was a Republican.

A RINO -- damn them! It would've made sense if he was some woke, progressive Democrat but, no, he dismissed it as something insignificant despite the fact that the Honorable Melville Weston Fuller, 8th Chief Justice of the United States, declared before a Joint Session of Congress;

“If we turn to this remarkable document and compare the line of conduct therein recommended with the course of events during the century—the advice given with the results of experience—we are amazed at the wonderful sagacity and precision with which it lays down the general principles through whose application the safety and prosperity of the Republic have been secured.”.

When President Trump was elected to his first term, I wrote him in hopes that he would show interest in President Washington's farewell but, alas, and despite a fair number of views, no response of acceptance or rejection was forthcoming. Thus, I was once again disheartened. I was amazed and flabbergasted that NOBODY in the Trump team apparently shared my reverence for His Excellency, the Most Honorable George Washington, the Father of Our Country. Again, just how deep has our country sunk???

I have had it up to my ears with the charlatans and scoundrels who pose in front of the American flag inside government buildings surrounded by barricades in armed guards in the District of Columbia who think George Washington's Farewell Address was a place where postal letter carriers delivered his mail -- else some useless, obsolete artifact that has no place in modern-day governance and international diplomacy -- and are steadfast in keeping His Excellency's final words to the American people flushed into the sewer as far down the drain as possible. I consider them to be THE GREATEST threat to our national security and survival. Chinese communists, Russia, North Korea, and Islamic jihadists have nothing over them!

They have besmirched and eradicated the FORMER glory of the name of Washington -- glory that was described by future-President Lincoln as follows:

“Washington is the mightiest name of earth -- long since mightiest in the cause of civil liberty; still mightiest in moral reformation. On that name, a eulogy is expected. It cannot be. To add brightness to the sun, or glory to the name of Washington, is alike impossible. Let none attempt it. In solemn awe pronounce the name, and in its naked deathless splendor, leave it shining on.”

Personally, I think the above words should be prominently and conspicuously engraved in a large block of granite between the Reflecting Pool and Lincoln Memorial so they can be read by visitors looking at the Washington Monument while visiting the former, but that's a subject for another day. Let's first get indispensable passages of the Farewell Address engraved in stone around the Washington Monument in accordance with the McMillan Plan so that it can never - EVER - again be brushed aside, ignored and forgotten. I don't know if the original plan provided for its inscription but the revised one certainly should.

(plenty of space for indispensable passages of the Farewell Address in this design)

At this juncture in my life, I have concluded that my patriotism and zealous reverence for the Father of Our Country and his final words to the American people [which I refer to as THE DIRECTIONS] on how to run the federal government and relate to other nations is attributable to the fact my namesake is Col. William Prescott, an early American patriot whose distinguished service in the Continental Army under the command of General George Washington was notable - particularly at the battle of Bunker Hill - and was such that it resulted in a statue and obelisk HALF THE SIZE OF THE WASHINGTON MONUMENT and President Trump's recent executive proclamation in recognition of its 250th anniversary.

Another member of the Prescott family, Samuel, made an important - yet unfortunately under-recognized - mark on history in furtherance of the cause of America {which was, AHEM, according to Thomas Paine, was a cause for all mankind};

... completing the mission of the legendary Paul Revere and his compatriots.

I have recently applied to join the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution and their representative has traced my ancestry to a Captain Jeremiah Prescott of New Hampshire who served in the militia. Membership has been approved pending submission of certain documents. I am so looking forward to hearing what they have to say about President Washington and his final words to the American people.

Thus, my passion for American liberty is therefore, quite literally, in my DNA and I like to think their spirit for American independence from tyrannical and despotic government lives in me. And, for the record, my definition of tyranny is based on that described by James Madison in Federalist 47 [incidentally, my reverence for President Jackson's farewell ranks right alongside that of President Washington's].

I think it would be particularly befitting for the West Virginia congressional delegation to sponsor my GEORGE WASHINGTON FAREWELL ADDRESS REVIVIFICATION AND PRESERVATION ACT - you in the Senate and my congressman, Riley [who has been contacted] in the House because, according to the US Senate historical office (details which have been deleted from the current version - perhaps you can have them reinstated) the distinguished gentleman from our state set a record which has yet to be broken.

Delivery generally takes about 45 minutes. In 1985 Florida senator Paula Hawkins tore through the text in a record-setting 39 minutes, while in 1962 West Virginia senator Jennings Randolph, savoring each word, consumed 68 minutes.

It is important to note that Senator Randolph savored each word because; “They are so meaningful” - per his handwritten entry in the Farewell Address Notebook. For you and Riley to bring forth this legislation would give West Virginians yet another thing to be proud of in regard to the history of His Excellency, the Most Honorable George Washington.

I don't think I shared this with you before but, just so you know how serious I am about President Washington's farewell address, please note this letter from Dr. Richard Baker, United States Senate historian:

Sadly, after hand delivering letters to all 100 senators' offices asking for assistance in my project, Dr. Baker, a TOTALLY fine gentleman who was sympathetic for my cause, was the ONLY one on Capitol Hill who shared my enthusiasm for the most important words to come from the hand of the Father of Our Country

I recently made yet another trip to Arlington National Cemetery seeking inspiration and to contemplate the service and sacrifice those grave markers represent. I feel pretty confident they didn't do what they did for a government that would eventually PHASE GEORGE WASHINGTON OUT OF WASHINGTON and relegate his final words to the American people to the ash dump of history in the farthest corner of the back lot.

Although I do not have any relatives or friends buried there, I feel like I owe them something - like a deep debt of gratitude and commitment to honor and remember just who was the Father of Our Country, and not tolerate his timeless admonitions to the American people for posterity being ignored and forgotten.

I suppose I should leave you with one of my favorite quotes from President Jackson's Farewell Address:

“... the lessons contained in this invaluable legacy of Washington to his countrymen should be cherished in the heart of every citizen ... his paternal counsels would seem to be not merely the offspring of wisdom and foresight, but the voice of prophecy, foretelling events and warning us of the evil to come.”

Repeat: “

PROPHECY...WARNING US OF THE EVIL TO COME”

Any questions?

From there, His Excellency went on to say;

“But if I may even flatter myself, that they may be productive of some partial benefit, some occasional good; that they may now & then recur to moderate the fury of party spirit, to warn against the mischiefs of foreign Intrigue, to guard against the Impostures of pretended patriotism -- this hope will be a full recompense for the solicitude for your welfare, by which they have been dictated.”

I don't think it is too much to ask for his immortal words to "now and then recur" -- "to be productive of some partial benefit, some occasional good" once every four years in a joint session of Congress. How about you?

This is a complete list of my goals.

Thank you for your time and attention.

Respectfully yours,

William Prescott Perry

Founder and Director